On January 23, 2026, the Carter G. Woodson Institute for African American and African Studies hosted a symposium honoring Dr. Reginald D. Butler. The event was occasioned by the recent publication of Dr. Butler’s manuscript, The Evolution of a Rural Free Black Community: Goochland County, Virginia, 1728–1832 (University of Virginia Press, 2025). What follows are my remarks (which I am still editing)) from the symposium.

Thank you for the opportunity to participate in this timely and critically important symposium honoring former Woodson Institute Director Reginald Butler, an intellectual visionary whose impact on the academic life of the University of Virginia remains as vital and enduring as ever. It requires no great leap of imagination, nor any twisting of facts to assert Butler’s profound influence as both an educator and institution builder. The seeds of his labor have blossomed magnificently across grounds. The upsurge in scholarship on slavery, racial exclusion and segregation, and African American life at the University of Virginia and the broader Charlottesville community, in addition to the many courses focused on Race and Place, attest to the depth and durability of Butler’s influence.

Long after his transition into the ancestral realm, his invisible hand continues to shape our intellectual work.

Through his groundbreaking scholarship, teaching, and collaborative endeavors, Butler illuminated the power of “local knowledge” as a hermeneutic device to understand more fully not just a geographical terrain but the human condition in all its complexity.

What Butler modeled, for me and so many others in Black Studies, was an integrated approach to field advancement in which archival research, curricular innovation, experiential learning, community collaboration, and public facing scholarship were seamlessly connected in service of knowledge production for human flourishing.

The magnitude of Butler’s institution-building efforts was not immediately apparent to me when I joined the faculty twenty-two years ago. Over time, however, I gained a deeper appreciation for his organizational acumen, his abiding faith in the power of collaborative work, and his distinctive model of institution building—one grounded in research projects and pedagogical innovation.

My comments today draw on five years of interaction with Butler as a colleague in the Woodson Institute and the Department of History; sustained engagement with, and reflection on, the commentary of his students and mentees who enrolled in his lecture courses and seminars; and careful examination of his research initiatives, including but not limited to the Race and Place Archive, Virtual Vinegar Hill: Preserving an African American Memoryscape, the Holsinger Project, the Emerging Scholars Program, and the Chesapeake Regional Seminar in Black Studies.. My reflections also bear the imprint of my ongoing efforts to understand the legacy of his institution-building work, the strategic choices that shaped it, and the lessons it offers for our current moment.

To say that Reginald Butler had a significant impact on my intellectual trajectory would be an understatement.

In 2004, he chaired the search committee that brought me to the University, where I held a joint appointment in the Woodson Institute and the History Department.

On my campus visit, he picked me up from the Amtrak Station, then we strolled to a restaurant on Main Street. Over dinner, we talked Garveyism, black nationalism, Black Studies.

Talking to Butler transported me back to my undergraduate years at Temple University. His teaching references conjured thoughts of Greg Carr while his listing of research projects ignited memories of Bettye Collier Thomas.

The conversation was easy yet invigorating.

It makes sense that our encounter felt easy, almost effortless.

The parallels in our lives were striking. Butler, who shares the same birthday as my father, had an intellectual journey analogous to my own, one that included basketball as a formative experience and Philadelphia as an important crucible and music as a source of endless inspiration and joy.

Within a week of my visit, I opted to make Charlottesville my home.

After my arrival at UVA, Butler continued to mentor, not smother, guide but not dictate.

In my first year, I observed his interaction with colleagues, his mentorship of undergraduates and graduates, his engagement with the local community, and his careful curation of the Institute’s many research projects.

At the Woodson in those days, the FTE’s were low, but the community was vibrant. There was Scot French and Butler, Corey D.B. Walker, Hanan Sabea, and Marlon Ross. There were graduate students and fellows, including Cheryl Hicks.

More importantly, there was a critical mass of undergraduates deeply committed to Black Studies as an intellectual project.

The vibrant intellectual world I inhabited in 2004 had been cultivated by Butler. He prioritized undergraduate education and viewed the advancement of Black Studies as an intellectual project dependent on not just the accruing of faculty lines but also the training undergraduates in the methods and theories of the discipline. UVA’s contribution to a Black Studies pipeline, he believed, must emerge not just from its internationally renown predoctoral and postdoctoral fellowship program but also from its undergraduate curriculum and student body.

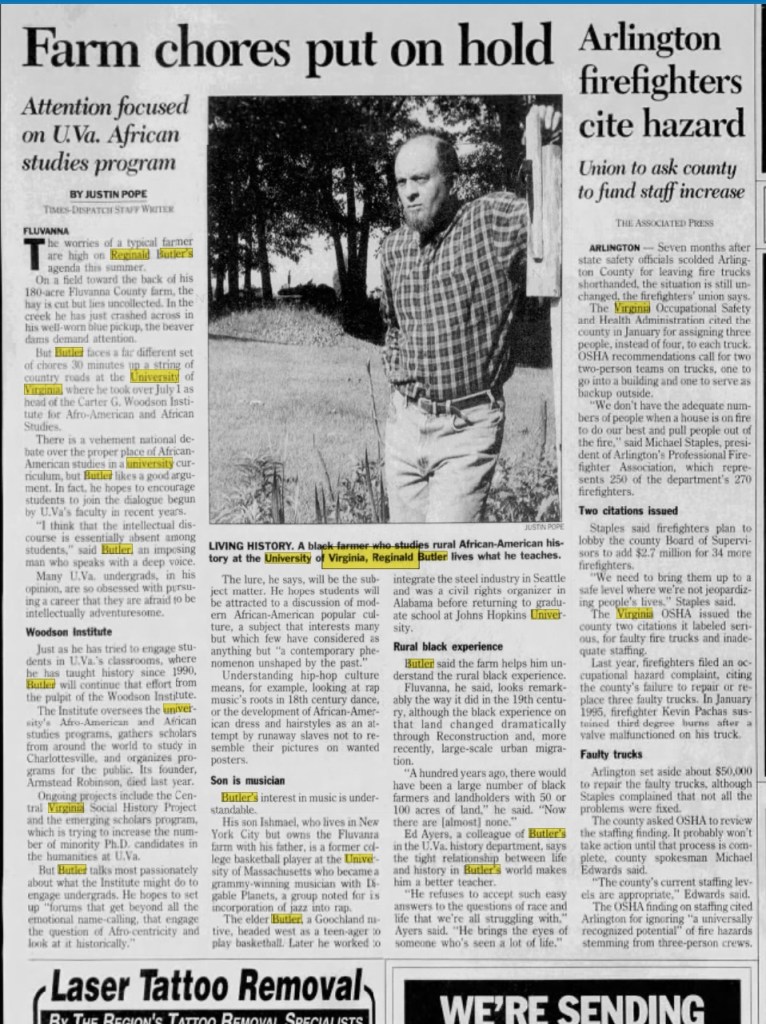

This commitment was evident immediately upon his appointment as the Woodson Institute’s director in 1996. In an article in the Richmond Times Dispatch, Butler was unequivocal in his commitment to strengthening the AAS major, as well positioning undergraduates at the center of the major debates about the direction of the field.

In sharing his plans with the Times Dispatch, he expressed a desire to “create forums that get beyond all the name calling, that engage the question of Afrocentricity and look at it historically.”

Of course, Butler had already been doing that important work.

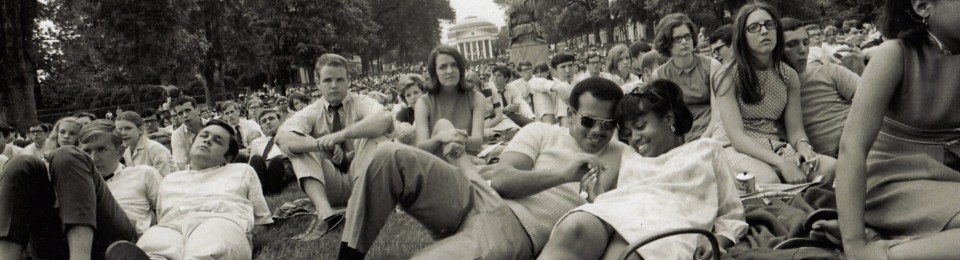

After joining UVA’s faculty in 1991, he connected immediately with undergraduates emboldened by political fervor of the times and negotiating a world of political contradictions and paradoxes.

What surfaces often in my conversations with former students of Butler is the portrait of a wise bluesman with a jazz spirit guiding the hip hop generation through the deep waters of African and African diasporic history, politics, and culture.

A match made in heaven.

When students began classes in 1990, there were 1,261 African American undergraduates, constituting 11% of the population. That number rose to 1,366 the next year. In fact, throughout the 1990s, the African American undergraduate population was never less than 10%.

Organizations flourished. BSA remained the heartbeat of Black UVA, Black Voices was incredibly vibrant with a membership of 200, and Black Greek organizations anchored social and culture life.

New organizations emerged—Black Empowerment Association, Black Enterprisers, the Paul Robeson Players—along with new traditions like Blackout, an annual spring event created in 1993 and still up and running.

This was a generation hungry for history or as we might say knowledge of self.

As Tiwanna Simpson observed in her editor’s note for the February/March 1991 issue of Pride magazine:

“We are all diligently trying to solve the mysteries of our family history, searching for the hidden secrets of black history.”

For hundreds of students, many of the mysteries of family history and the hidden secrets of Black history were revealed in Butler’s class.

“He was the consummate intellectual,” Professor Cheryl Hicks recalled in a recent conversation.

Embedded in Reginald’s undergraduate work and mentorship was the belief in the dignity and intrinsic value of everyone, a conviction that every student has a singular gift, and that institutions of learning bear a responsibility for nurturing that gift.

Looking across the arc of Butler’s tenure at UVa, it becomes clear that the first half of the 1990s was critical in molding the philosophy of teaching and undergraduate mentorship that significantly informed the research enterprise and apparatus of the Woodson Institute after his appointment. With the Institute’s research projects and initiatives, he had the opportunity to elevate his pedagogy to another level.

Within a short time frame, Butler initiated an impressive array of research initiatives, including the aforementioned Race and Place Archive, the Chesapeake Regional Seminar in Black Studies, the Holsinger Project, and the Emerging Scholars Program.

This work was intentionally public facing; for example, in 1998, Butler called on community members to help identify photos from the Holsinger collection, explaining to the Daily Progress, “What we want to do is examine these 500 photos within a race and class context,” Butler told the Daily Progress.

Butler’s exceptional work quickly gained national attention. “The Carter G.Woodson Institute for Afro-American and African Studies at the University of Virginia (UVa) has been reinvigorated and reconceptualized in the short time since Reginald Butler was named Director in 1996,” Dianne M. Pinderhughes and Richard Yarborough raved in their 2000 review of Ford Foundation-Funded. Butler, the review concluded “ has proven to be a forceful and effective director.”

Indeed, there was much to admire about Butler’s leadership. His integration of the Institute’s research and teaching endeavors was quite impressive as the unit’s archives became critically important pedagogical tools. In one of seminars, for example, students worked on the Race and Place website, processing, and synthesizing data.

Out of these classes emerged DMP theses, writing samples for graduate application, and long-term political commitments.

As an educator Butler understood the necessity of intellectual rigor, discipline, and accountability within the classroom, but he also recognized importance of extending his mentorship beyond grounds, which entailed involving them in conducting oral histories, presenting their findings to the larger public, and developing their own projects and theories.

Butler’s integrated strategy of field advancement was a model for me as I begin working on Black Fire. Since 2012, I have been involved in a multidisciplinary, multimedia project called Black Fire, which explores the history of African Americans at the University of Virginia from the 1960s to the present. The project’s film series,

website, and the accompanying lecture course that involves students conducting interviews and competing group project bears the unmistakable imprint of Butler’s influence.

Admittedly, my remarks today are shaped by my commitments as, first and foremost, a teacher of undergraduates; as an administrator working within higher ed’s evolving landscape; and as a scholar committed to the Africana work of recovery and translation.

These intersecting roles have only deepened my belief in the urgent relevance of Black intellectual traditions, the need to safeguard the spaces where they are cultivated, and the need to remember those who modeled visionary and sustainable approaches to institution building.

So I’m deeply thankful for today.

The enormity and urgency of our current moment demand spaces like this—spaces for critical reflection, principled dialogue, and collective imagining. As Vincent Harding reminds us in his essay “The Vocation of the Black Scholar,” we are in need of “liberated ground on which to gather, reflect, to teach, to learn, to publish, to move toward self-definition and self-determination.” It is in that spirit that I join this gathering and hopefully future events—with a deep sense of responsibility, solidarity, and hope.

Thank you!

This was a gre